Britannia Hospital: Bad Timing

- Charles Drazin

- May 24

- 5 min read

Updated: May 26

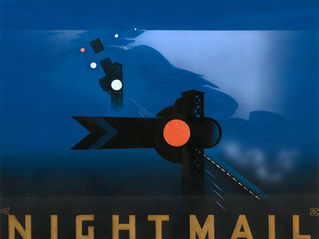

It was a brilliant, shocking poster that made you sit up if not lose your head. The trouble was that eight thousand miles away British soldiers were now in serious risk of losing theirs as the Falklands War approached its climax. The release of Britannia Hospital at the end of May 1982 could not have been more disastrously timed. In an effort to limit the damage, the producer and distributor of the film, EMI, ordered that all copies of the poster be destroyed. A dull, typographical poster was put out instead.

“If the EMI circuit can do nothing else, they at least know how to shred,” observed the film’s director Lindsay Anderson when he sent a copy of the original headless poster that had escaped the holocaust to his friend the Times film critic David Robinson.

Rather than release the film at such an explosively inopportune time, it would probably have been wiser to have shelved it for a while, but lacking the benefit of hindsight, EMI pushed on with its plans for a big nationwide release.

The film’s vision of a warring, polarized humanity about to surrender its future to a dangerously fallible artificial intelligence seems chillingly prescient today. But it was not the kind of warning that a 1982 Britain, in the grip of war fever, was ready to hear. Lindsay was able to judge the mood for himself when, in the weeks before the film’s release, he went on a promotional tour of the country.

While he was in Newcastle, he visited the Laing Art Gallery, where a painting by the eighteenth-century romantic artist John Martin caught his eye. It depicted the last of the Welsh bards cursing the English from a high rock before flinging himself to his death.

Having long imagined himself as more Celtic than English, Lindsay recognized a kindred spirit. He bought a postcard of the painting, which he sent to his close friend Lois Smith: “There will be many people who will dislike Britannia extremely,” he wrote to Lois on the back: “Bards and prophets have always been called loonies – or worse!”

The postcard was dated 18 May. Only the week before, on 10 May 1982, the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Sheffield had sunk in the South Atlantic after having been hit by an Exocet missile. Then, on 21 May, 3 Commando Brigade, landed in the Falklands at San Carlos Water. As the British soldiers left their beachhead to yomp across boggy, rough terrain, Lindsay faced his own battle on the beaches of the Cannes Film Festival.

Britannia Hospital was screened there on 24 May. It received a gratifyingly positive reception, with many people in the audience applauding the film. But its scathing depiction of Britain at such a time made it an obvious hostage to fortune.

The Daily Express took full advantage: “Someone always gets hurt in a war,” wrote their man in Cannes. “And that sad truth could soon hit home to British film director Lindsay Anderson. In the thick of the Falklands conflict ... he is marching into cinematic battle with a film that MOCKS us.”

The piece, which was published only two days before the film’s UK opening, anticipated the mostly hostile response of the British press. Few people went to see the film, which quickly disappeared from Britain’s screens.

Three months later, in August 1982, an upset but fatalistic Lindsay confided his thoughts to David Robinson in a long letter. “You know, it’s not the antagonism that wounds or disappoints, nor the “failure”. It’s the lack of support. With arts like the cinema and theatre, there’s a limit to the length of time it seems worthwhile – or even possible – to go on when what one has to communicate can only fall upon ears so determinedly deaf.”

Robinson had not reviewed Britannia Hospital for The Times when the film came out. The job had been given instead to his colleague, Geoff Brown, who wrote a luke-warm piece. While acknowledging that “for much of the film his savage style pays dividends”, Brown complained that “Britannia Hospital never finds a sufficiently strong focal point; Millar’s concluding jeremiad about the awful ways of the world leave only an impression of humanistic huff and puff. After two hours, one emerges half stimulated and half maddened by the film’s sheer belligerence.”

With his flair for belligerence, Lindsay had not forgotten the review, and he brought it up in his letter to Robinson: “Your doppelganger’s description of Dr Millar’s peroration: ‘…the old humanistic huff-and-puff’. What contemptible depths of shallowness the comment reveals.”

Robinson would soon have a chance to make amends for his colleague. In October 1982 the film briefly resurfaced in London. It was only on one West End screen, but still he made the most of this opportunity to put in a word for Lindsay. “Let us return to Britannia Hospital,” he wrote. “[T]he press (with a couple of exceptions) was so damning that no one was surprised when the public stayed away. The film was rapidly taken off the screens. Only now, five months later, does it re-emerge for a second try at the brand new Classic in Tottenham Court Road.”

The review that followed was glowing. Although Top Ten was not a game that Robinson played, Britannia Hospital was a “masterly film” that he would “unhesitatingly include” in his list of all-time Top Best Films. The words, Lindsay knew, were as much those of a friend seeking to be supportive as a critic’s objective appraisal, but that made them all the more precious. “You take my breath away,” he wrote to Robinson, “but, yes, that is the way to play those silly games. This time you really have used those shining quotable words, and I’m v. grateful and whole-heartedly appreciative. Perhaps the tide will turn…”

The tide turned a little when the film was released in the United States at the beginning of 1983. More shiny, quotable words. The New York Times critic Vincent Canby wrote: “Britannia Hospital is an outrageous satire on an empire’s decline and fall and nearly everyone’s refusal to face the situation… No secret is made of the fact that Britannia Hospital is a metaphor, but the reason the film works with such consistent funniness is not its satire, which is devastating, but the expertly staged and acted farcical complications that turn this day of celebration into a glimpse of the apocalypse… Britannia Hospital, Mr Anderson’s best film to date, is far more successfully integrated than the two preceding satires” – i.e., If.... and O Lucky Man! “Though the subject is national exhaustion, the effect is immensely bracing.”

Perhaps it needed a foreign critic to get to the heart of the film. After all, it couldn’t be quite so enjoyably bracing for the British, because they were the chief victims of its unflinching honesty. I think the film failed in Britain for the same reason that Jean Renoir’s La Règle du jeu had failed when it was first shown in France. It attempted to show a society that was falling apart, but, as Renoir himself observed, “this is something that people do not like; the truth makes them feel uncomfortable.”

La Règle du jeu would eventually secure a firm place in the canon of the greatest films ever made. I’m not in the game either of playing Top Ten, but I do think that, more than forty years on, the truths of Britannia Hospital have become only more evident. Lindsay was trying to warn of the folly that threatened us. We ought to have listened then as it’s become only more urgent that we listen now.

Lindsay’s fate was Cassandra’s fate, an irony that, as a former classical scholar, he would surely have appreciated:

tunc etiam fatis aperit Cassandra futuris

ora dei iussu non umquam credita Teucris.

– Virgil, Aeneid 2.246–7

You know Charles, that that flag-waving headless figure was made by me: a "lino cut" (cutting a picture into now superceded linoleum flooring material, and then inking the remaining uncut linoleum with a roller, to make a print).

The large blue circle was originally the outline of one of Lindsay's dinner plates. I was 22 at the time. Seeing what I'd come up with ("𝘞𝘩𝘺 𝘤𝘢𝘯'𝘵 𝘩𝘦 𝘨𝘳𝘢𝘴𝘱 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘜𝘯𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘑𝘢𝘤𝘬 𝘮𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘧𝘪𝘳𝘮𝘭𝘺, 𝘚𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘺?" I couldn’t answer back at the time, but in hindsight I can say now it was because I wanted him (it?) to hold the flag in that effete half-hearted way you'd always see people do at royal events, when say, the Queen and some family memb…