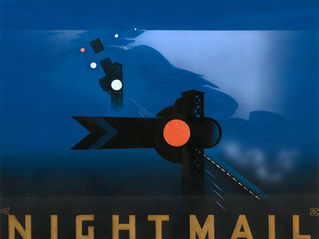

Night Mail at Ninety

- Charles Drazin

- Dec 15, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: 7 days ago

It was 1935. Only nineteen years old, Pat Jackson, who was assistant to the film’s co-director, Harry Watt, was waiting for the Night Mail with Watt and the cameraman Jonah Jones on the summit of Beattock. Over a thousand feet above sea level, the hill was the highest point on the West Coast Main Line.

Pat – who would go on to direct the great wartime drama documentary Western Approaches – described the occasion in his memoirs: “It was cold, I remember, and we played rugger with my battered old trilby to keep warm, and then she appeared miles below us. Two puffing funnels were shooting white smoke up the valley for there was a pusher to help the climb.”

The detail about the trilby reminded me of our snooker matches at the Savile Club. Pat was a keen, competitive sportsman, but also an excellent coach who was faultlessly encouraging in spite of my lack of aptitude for knocking balls around the green baize.

Born in 1916, Pat belonged to a generation that had been tempered by two world wars. One of his earliest memories as a child, he told me, was seeing a railway engine pull a long train of wrecked tanks that had been salvaged from the Great War. He grew to adulthood under the shadow of the next war, which, as the 1930s wore on, most people feared sooner or later. The British Documentary Movement, which gave him his training, fostered a social-realist approach to the cinema that the outbreak of war in 1939 only further encouraged.

With the atmosphere of the times shaping the boundaries of public taste, Night Mail was an important landmark in the cinema for suggesting that aspects of everyday experience – as, believe it or not, posting a letter still was in 1935 – could be of mainstream appeal. Previously, documentary films had been shown in film clubs and lecture halls. But Night Mail was unusual in also receiving bookings from commercial cinemas. Pat remembered that its first public showing took place as part of an opening gala event for the new Cambridge Arts Theatre in February 1936. “There was enormous applause at the end,” he recalled. “We were all sitting there, and we looked at each other with astonishment, thinking, ‘My God, it’s coming off! It must be quite good!!’”

In March 1936, it was on the programme when the new Harold Lloyd comedy, The Milky Way, opened at the Carlton in the West End. It was, Graham Greene wrote in his review for the Spectator, “one of the best films to be seen in London”. He singled out as “extraordinarily exciting” the “final sequences as the train drives at dawn through the northern moors, the sheep-dog racing the train and the rabbits scurrying to cover, set to the simple visual verse of Mr Auden”. Deserving equal credit for the sequence was a young Benjamin Britten.

Having worked successfully together on Night Mail, the poet and composer soon afterwards began another collaboration. The Ascent of F6 was a play that opened in February 1937 at the Mercury Theatre, Notting Hill Gate. In its finale was an another Auden poem that Britten set to music: “Stop All the Clocks”. It was used to satirical effect in what was a political play, but Auden shortly afterwards, adding new verses, transformed the poem into an elegy of loss.

This reworked version features in the one funeral that takes place in Four Weddings and a Funeral. The character Matthew (John Hannah) reads it out, as he stands before the coffin of his partner Gareth (Simon Callow).

“[It] is well worth looking at, for research,” Lindsay Anderson told me soon after the film had come out in 1994. “I don’t need to tell you that I disliked it a lot.” We had arranged to meet after he got back from a holiday in France – I was writing a book, for which he had agreed to be interviewed. But he had a fatal heart attack and never did get back.

When I saw the film, it was easy to understand why Lindsay had disliked it. “No film can be too personal,” he had written in the Free Cinema Manifesto. “An attitude means a style. A style means an attitude,” But Four Weddings and a Funeral was an example of a film with lots of style but no attitude – or at least not any that was going to be allowed to get in the way of a good laugh (or cry).

It was the second time that Auden had been involved in a significant landmark of British film history. But if Night Mail was a cradle for social-realism, Four Weddings and a Funeral was the grave that Working Title dug for it sixty years later. It was a lush, enjoyable but wilfully vapid romantic comedy that stood in sharp relief to Working Title’s very first feature film, My Beautiful Laundrette.

The astonishing worldwide box-office returns of Four Weddings, $245,700,832 (according to Box Office Mojo), meant that there would be no going back. Along the lines of its success Working Title (soon to find a comfortable niche within a major Hollywood studio) built an efficient production line of similarly entertaining but inconsequential films for the international market.

Released soon afterwards, Shallow Grave – a triumph of spectacle over realism – dug the grave even deeper. And then, in 1996, the follow-up of an undeniably talented film-making team served up the carcass of social-realism Cool Britannia-style, as with Trainspotting a noble but defunct tradition was ingeniously repackaged to appeal to the readers of Loaded.

In that strange, fairytale time of the 1990s when history was even briefly said to have ended, we had the luxury of not having to worry about global conflict. But thirty years on, we know that the clocks can’t stop until history really has ended, and that the train of wrecked tanks that Pat Jackson saw as a small boy in the aftermath of the Great War still has its relevance.

Meanwhile Stop All the Clocks – an irresistible title for the latest repackaging of Auden – is back in the bookshops in time for Christmas. As the Faber blurb puts it: “Poetry to reach for in times of turmoil.”

Comments