London Can Take It!

- Charles Drazin

- Apr 28

- 11 min read

As “America First” 2025 approaches the heights of alarming insularity, it’s worth thinking back to 1940, when, in spite of the same ostrich instinct, enough Americans realised that what was happening elsewhere in the world really did matter. After some hesitation, the United States used its huge power to change the world for the better. But it had required some persuasion.

Part of that persuasion was London Can Take It! It was a short film that depicted the plight of a large capital city under massive aerial bombardment at a time when such a thing was still a horrifying novelty for the world. The London of September 1940 became what Kiev is today: a city on the front line of a fight against tyranny.

Thirty years ago I interviewed Joe Mendoza, who had worked on the film as a nineteen-year-old cutting room assistant at the GPO Film Unit, which was very shortly afterwards to be be re-named the “Crown Film Unit”. His memories of that time were vivid and detailed.

In charge of the GPO Film Unit was the Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti. But once the Ministry of Information had taken over at the beginning of the war, everyone knew that Cavalcanti would soon have to leave. As Joe put it, the government did not think that a “Brazilian, communist, surrealist, homosexual aristocrat” was a suitable person to head an organisation responsible for making films on their behalf. When he eventually moved on to Ealing Studios in the summer of 1940, Ian Dalrymple, who had worked previously as a screenwriter in feature films, was chosen as his replacement.

With very little experience of documentaries, Dalrymple was inclined in those early days to defer to the film-makers of the unit. It meant that in this time of extreme crisis, as the Battle of Britain was being fought overhead, there was a strangely egalitarian atmosphere. Everyone mucked in without feeling there was anyone who was actually in charge.

That summer Joe was asked to act as an assistant to the director Charles Hassé, who was making a short film about the role of the police in wartime. “I thought of the title!” he told me: War and Order. He remembered a day in early September when he was with Hassé somewhere in the Kent hopfields trying to film a policeman catching a German bomber pilot. On the horizon, the sky had erupted into flames. It was the day the Blitz had begun. “It was awful,” he remembered, “to be away from home and mum and seeing nothing but the red glare from London.” In the days that followed, he would often sleep on the floor of Hassé’s flat in Hammersmith when the bombing made it impossible to get home.

Once it became clear that the bombing was not going to end any time soon, the Ministry of Information commissioned the newsreel company British Movietone to make a film about the Blitz. Harry Watt, a senior director in the GPO Film Unit, was asked to look through the footage and to help Movietone pull the film together. “I went with him to take notes and make a list,” recalled Joe. “Well, the long and short of it all was that Harry thought it was all crap ... and said we should tell the MoI we’d do it ourselves.”

The MoI agreed that British Movietone would provide its footage, at a £1 a foot, which the GPO Film Unit would then edit into a film. But in practice, the unit shot its own fresh footage, considering the newsreel material to be unusable. Although Harry Watt effectively took charge of the production, he described the film as a collaboration by the whole unit: “Off people would go into the heart of it to get fantastic shots and to be there, of course, as dawn came up, before all the real damage was cleared up. Everybody was sent round looking for people just carrying on.”

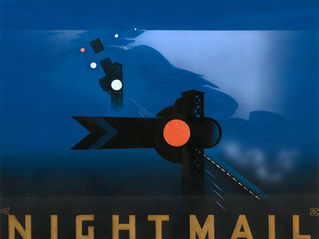

One of the film-makers who went out was Pat Jackson. He had joined the GPO Film Unit in 1934 straight from school. Two years later, he was one of the crew that was waiting to shoot “the Night Mail crossing the border, bringing the cheque and the postal order”. He told me how they had whiled away the time playing rugby with his hat. The anecdote captured for me the team spirit that the unit now displayed in shooting the Blitz: all for one and one for all.

Pat remembered a day in late September when the unit’s three cameramen were already out in London shooting with other directors. Hearing the drone of approaching bombers, he grabbed a Bell & Howell hand-cranked camera from the unit’s studio in Blackheath and, roping in the editor Stewart McAllister to help, loaded a thousand-foot magazine with film. As neither of them had driving licences, another editor, Gordon Hales, drove them to Greenwich Park, from where they filmed the raid.

Pat described the episode in his memoirs: “We set up the camera close to the Observatory and looked down on London. To the left, St Paul’s, serene as ever. Canaletto could have been painting it, so calm and peaceful was everything. To the right it was a different story. A massive range of mountains had suddenly heaved its way through the earth’s crust in London’s dockland. Dense smoke as of a gushing oil-well was climbing higher and higher, and soon the base became suffused with red as the intensity of flame increased by the minute. The clanging of fire engine bells was just audible. I cranked the camera handle at the same speed as the organ grinders of my childhood.” They then drove down to the river. “We waited a bit, wondering where to point the camera. It didn’t seem to matter. Wherever we pointed it was flaming hell.”

But there was no authorisation from the Ministry of Information for the GPO Film Unit to shoot any of this new material. “It was all completely unofficial,” recalled Joe. “That was what the GPO Film Unit was like. They just said, ‘Oh fuck you, we’ll do this,’ and they did it... As far as the Ministry of Information was concerned, we were making a film about the London Blitz from newsreel material.”

Combative, anti-authoritarian and temperamentally disposed to action, Harry Watt took pride in what he called an ‘instinctive talent for dramatic journalism’. Consciously anti-intellectual, he was as down-to-earth as he was sometimes earthy. Joe remembered Watt once calling him “a silly little public school cunt” in front of the whole unit. “I didn’t mind the last word but I felt very resentful because the moment I joined the GPO I carefully massaged down my West Kensington voice to South London.” On another occasion, he overheard Cavalcanti losing his temper during a conversation on the phone with Watt, “screaming out in his unimitable accent: ‘In seven years I have taught you how to be a film director but I can never teach you to be a shentleman!’”

Watt may have been no shentleman, but he warmly acknowledged the lessons he owed Cavalcanti. One of them was: Don’t wait. When the Ministry of Information had taken over the unit at the beginning of the war, it didn’t know what to do with it. “Nothing happened for six weeks,” Watt remembered. “Then Cavalcanti took it upon himself to send us out. This is where Cavalcanti was great. He said, ‘History is being made. We can’t just sit here.’”

“Nobody realizes how important Cavalcanti was,” commented Joe. “I was just a boy sitting at the back of the theatre. But I used to listen like crazy. Cav would look at a cutting copy and say it is not any good. The first three minutes is fine, the last minute is very good, but it is the middle! It doesn’t have any shape. We must think of some movement to give it some shape. Cav got people to think analytically about what happened on the screen: it was good there, and it was good there, [but] what was wrong with the whole. That was the way Cav trained people. ”

As the Blitz film began to be assembled out of all the raw material, the creative weight of shaping the film fell on the shoulders of Harry Watt and Humphrey Jennings, and their respective editors. “I was the piggy in the middle,” said Joe. “I was the assistant to the two editors and the two directors. Everything would come in and I would sort it out.” The structure was the progression of a typical raid from dusk to dawn, and then its aftermath. “Harry did everything from the beginning of the raid to the dawn, and Humphrey and McAllister did [everything] after the raid.”

Because of the bombing, the unit had been moved from its studio in Blackheath to Denham Studios in Buckinghamshire, where it was given a new name, the Crown Film Unit. But, observed Joe, “They always used to call us the Half a Crown Unit because we had no budgets.”

Nora Lee, who then worked in Denham’s film library, remembered the amazed reaction of the dwindling well-paid staff of London Film Productions. They were winding down after their boss, Alexander Korda, had transferred the company’s super-production, The Thief of Bagdad, from Denham to Hollywood. While they enjoyed their last weeks of well-paid idleness, they watched in amazement as this bunch of penniless documentary film-makers headed off day after day back into town to film London burning.

Supervising the film for the Ministry of Information was Sidney Bernstein. As owner of the Granada cinema circuit, he had been appointed to advise the Films Division on distribution and exhibition. When he saw the rushes, he suggested that a friend of his, the American journalist Quentin Reynolds, then associate editor of Collier’s Weekly, should provide the commentary. “Sidney felt that what he called my ‘lazy, tired’ voice would, by underplaying, make the presentation more effective than would the polished style of the conventional English commentator,” Reynolds recalled. The even more important reason was that an American viewpoint would help the MoI to get the film into American cinemas at a time when the Neutrality Acts still prevented the US from giving Britain official support.

It was Reynolds who suggested the final title of a film that was originally going to be called London in the Blitz. “Since it seemed to me that the title should be as informal as the narrative, I suggested a revision to London Can Take It.”

Reynolds sat down with Harry Watt to write a commentary. “He wrote reams and reams,” recalled Watt, “and I would pick out the stuff that fitted.” Because Reynolds had never broadcast before, Watt arranged a test for him at Denham Studios. At first, it did not go well. “Jesus, what are we going to do with this ham?” thought Watt as the journalist bellowed into a microphone. But then the sound engineer, Ken Cameron, suggested that he be made to sit down in an armchair and whisper. “Suddenly this magnificent voice came out, a great, deep voice.”

I’m speaking from London. It is late afternoon and the people of London are preparing for the night. Everyone is anxious to get home before darkness falls. Before our nightly visitors arrive. This is the London rush hour. Many of the people at whom you’re looking now are members of the greatest civilian army ever to be assembled. These men and women who have worked all day in offices or in markets are now hurrying home to change into the uniform of their particular service. The dusk is deepening. Listening crews are posted all the way from the coast to London to pick up the drone of the German planes. Soon the nightly battle of London will be on. This has been a quiet day for us, but it won’t be a quiet night. We haven’t had a quiet night now for more than five weeks. They'll be over tonight. They’ll destroy a few buildings and kill a few people, probably some of the people you are watching now…

The impact was electrifying. The words he used were not “they” and “them”, but “us” and “we”. He called himself a “neutral reporter”, but what he showed demanded that any decent human being put aside their neutrality: that they admire and care about these people, who were so obviously fighting an evil that had to be fought.

With the film skilfully tailored to win over an American audience, the Ministry of Information arranged for its distribution in the United States through Warner Bros, which had adopted an actively anti-Nazi, pro-British stance since the beginning of the war. “I am unequivocally in favour of giving England and her allies all supplies which our country can spare,” declared its company president, Harry Warner. “The freedom which this country fought England to obtain, we have to fight with England to retain.”

Flown to New York on Tuesday 22 October, London Can Take It! opened in several big Broadway cinemas on Thursday 24 October. On the same evening President Roosevelt gave a radio address to the nation. The way he spoke suggested that he had already seen the film even if he did not mention it by name. Dwelling upon the threat to freedom and democracy, he commented: “We see, across the waters, that system undergoing a fearful test. Never before has a whole, free people been put to such a test. Never before have the citizens of a democracy – men and women and little children – displayed such courage, such unity, such strength of purpose, under appalling attack.”

Only a week after its opening in New York, the film was given a national release. It was shown in 1,000 cinemas, which, according to the trade paper Film Daily, marked “a record-breaking number of simultaneous engagements ever set on any film”. It would eventually be seen by an estimated 60 million viewers.

In early 1941, it was nominated for an Academy Award as Best One-Reel Short Subject. No separate category for Best Documentary then existed. If, on the night of the Oscars ceremony, 27 February, it lost out to Quicker ’n a Wink, an MGM short about strobe photography, perhaps it was because a film about the war in Europe was an awkward challenge for a country in which isolationist sentiment was still strong.

But the wartime partnership was now secure. Roosevelt had won a new term of office in the presidential election of November 1940. Although the United States remained officially neutral, the Lend-Lease Act was passed in March 1941. Then the following August Britain and the United States agreed the principles of the Atlantic Charter, which included “the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live”. It is a principle that the United States continued to assert over the next eighty-five years. So it is a shock to think that the world’s most powerful democracy might be about to turn away from it now.

Most films matter very little. In fact, the way the world works, it’s often the films that matter the least that profit the most. But every now and then a film that really does matter is able to make a difference. It happened in 1940 when the GPO Film Unit made London Can Take It!

But whether it can still happen is finally up to us.

Two months ago No Other Land, about the forced displacement of Palestinian villagers from their land in the West Bank, won an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. The way it had been made, in circumstances of great adversity, reminded me a little of the “All for one, one for all” spirit of London Can Take It!

“On the Oscar stage, I had a taste of power and possibility,” one of its four co-directors, Hamdan Balal, wrote in The New York Times a few days ago. He saw that a film could be used to convince the world that something needed to change. But it didn’t stop him from being beaten up by settlers when he returned home. He ended his piece: “I know that there are thousands and thousands of people who now know my name and my story, who know my community’s name and our story and who stand with us and support us. Don’t turn away now.”

Comments